Notes of the Tool Design Roundtable at Devcom (Gamescom Dev) 2025

For those who have never attended a roundtable before: This is a room filled with mostly game developers, from both big studios and indie studios, as well as non-game developers from manufacturers, TV, movies, third party software developers, and service providers. The folks in the room ask questions, and then anyone in the room can raise their hand to answer those questions, not just a speaker or panel of speakers. This conversational element makes for an environment in which everyone at the roundtable is brought together to discuss topics that they prefer, for how long they prefer. These sessions are not recorded. The notes below are unfiltered and written down after the fact from memory and shorthand notes, so always take them with a grain of salt.

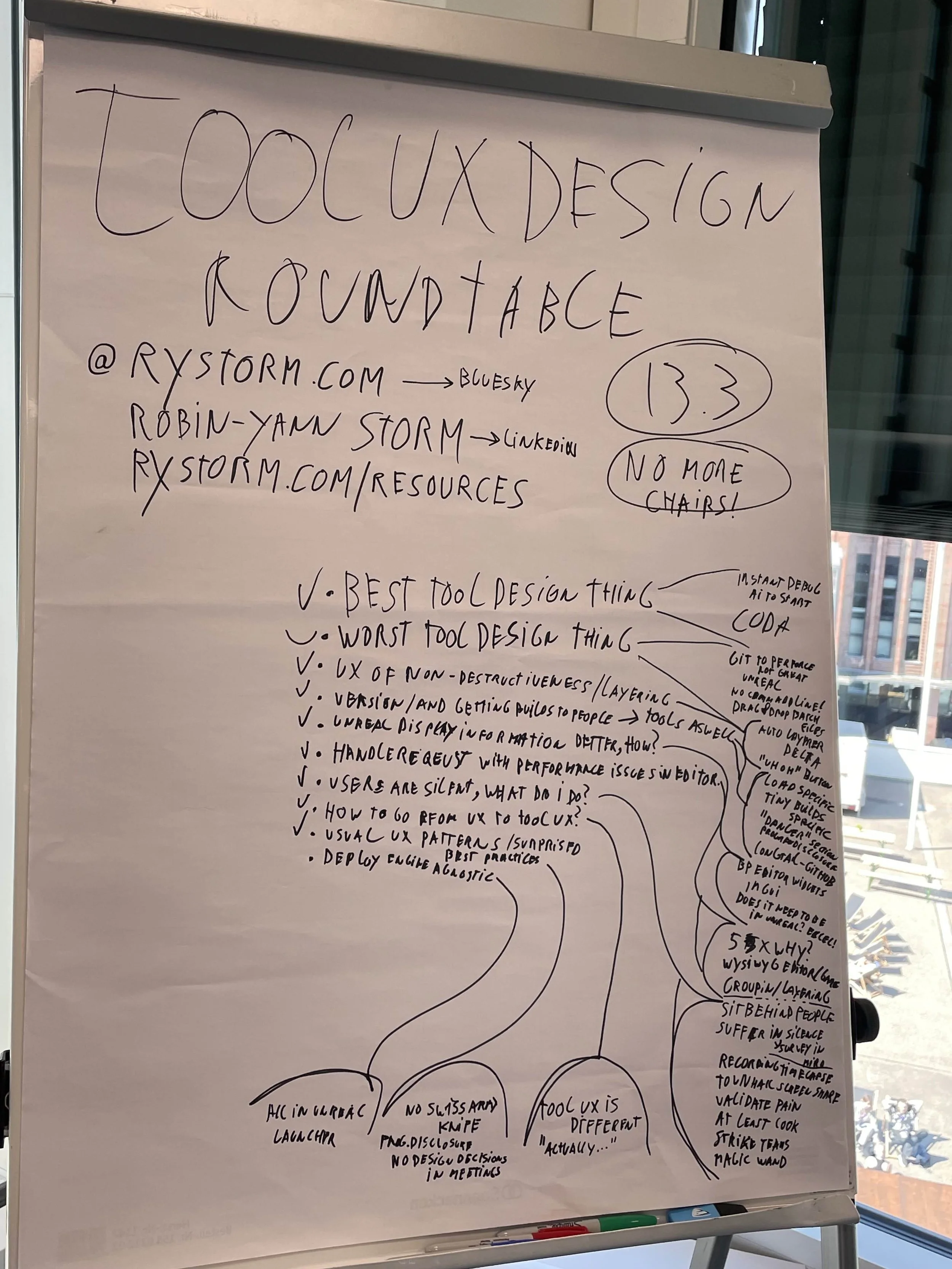

This roundtable was was held at Devcom (Gamescom Dev) in August 2025, for an hour and a half. The topics were:

Best Tool Design Thing this year

Worst Tool Design Thing this year

The UX of non-destructiveness / layering workflows

Versioning and getting builds & tools to users

Displaying information in Unreal, how can you make it better?

How to handle requests that will cause performance issues

My users are silent, what do I do?

How do I move from a UX design role, to a Tool UX Design role?

Usual Tool Design patterns, best practices, and surprises

How to better deploy engine agnostic tools

1. Best Tool Design Thing this year

Someone had built a workflow to more easily debug issues: A system that instantly has all the information ready of where an issue happened, how it happened, and which has a log ready with more information. This made it much simpler for everyone in the studio to file reports, as when someone has an issue, they do not have to fully write down all the detailed steps of what happened, and they can instead immediately create a ticket. The log is then automatically added to the ticket and indicates the actions the user has taken, in which situation the user was, etc. This was really helpful for everyone in the studio as nobody wants to spent 15 minutes recollecting what exact actions they were taking before a crash, issue, or bug happened. Users are busy enough with their work to try and remember every single button press they did. Besides, Nvidia ShadowPlay and other video recording systems make it much easier to see what a user has done without asking them to recollect it. For example by allowing for a continual 1 minute to 10 minute recording. If you instead require everyone to write down detailed reproduction steps, those steps will be wrong a lot of the time as human cognition is fallible. Even worse: The ticket may not be written at all because who has time for that next to their regular deadlines? Which is a terrible reality, but the reality we have to work with.

Another topic that was brought up was using AI to start when initially building content. For example: If there is a blank space, to initially fill it up with something from AI generation, even if that generated content is terrible, to get away from the ‘blank page problem’. The example used was an ‘initial generation’ of things such as UI to give people something to start thinking from if they are working on UI. However, other folks mentioned that this often required removing everything that was generated at a later time, and that the removal of such content can be tough if it is interwined with your own created content. If that is not properly done, it can be overlooked later, which creates sharp contrasts in quality. Some at the roundtable still found that to be faster than starting from a blank page, while others thought it was too dangerous and messy to start off with and that there are better ways to start from scratch, such as with team discussion or simple doodling.

2. Worst Tool Design Thing this year

For the worst thing, someone mentioned that there is a plug-in to ‘kind of’ allow Perforce to be used in Unreal, but that this was generally not great to use. A few people then spoke up and complained that version control for Unreal was generally hard to use, and that there are no great workflows for it. That even with any version control software, including Git, UI’s like SourceTree, and others, it was still easy for users to mess up versions, submit the wrong things, get into conflicts within the team, and many more issues. It was honestly a bit surprising how folks from many different studios around Europe were entirely and immediately aligned with their loathing for version control workflows and Unreal. I then asked the room if anyone was happy with their version control workflow for Unreal, and nobody raised their hand, which made folks laugh. It seems Unreal has strides to make here.

Another thing is that someone mentioned command lines do not work well for non-technical people. In their case they had made a command line system, gave that to some of their designers, and it that did not work well for them as they often got stuck, asked questions, and could not easily use it on their own. The designers found it really difficult to use, even with only a few commands available, and even if they were ‘simple’, or at least simple to what an engineer considered simple. They asked if anyone had a solution, and someone brought up that what really worked well for them was to use drag & drop batch files instead. The batch file is still a command line approach, but in a batch file workflow the end user can simply drop whatever files they need onto the batch file and then the command line automatically actives commands on those files. So the users does not have to see or copy paste anything into a terminal command line UI, and it works correctly automatically. This made it possible for the batch files themselves to still be simple to create for engineers, with no UI being necessary to be built, while keeping non-technical users happy with an easy drag-and-drop workflow.

3. The UX of non-destructiveness / layering workflows

The question essentially was: How do you make sure that folks can do their work without needing to be destructive with their content, especially when it comes to generative worlds? For example: If users want to return to a previous version of a terrain, how do you do that in a good way, as usually generating a new version of a terrain destroys the old version. One method mentioned to get around this was by using auto layering: Allowing the user to easily layer what they have so they can quickly enable and disable what they are actively working on. So in this case of terrain generation to automatically save the old version of the terrain on one layer and hide it, and automatically place the new version of the terrain on another layer and show that. Then the user can work non-destructively by having those layers as backups, or even override one another if you are using a scene format like OpenUSD. Users can then also change individual layers without adjusting the final layer, similar to workflows such as the ones in Photoshop. Also, when it comes to destructive workflows, at the GDC 2024 Tool Design Roundtables this topic came up too, and the conclusion from it was: Why be destructive? Hard drive space is generally cheap, so why not save it or back it up somewhere, so a user can return to it in the future?

Another mentioned method was to be very clear to the user about what has been changed. For example, if they start working on a particular area and then after a couple hours they are done, you could build a feature in your 3D editor that allows them to see the delta between what they had, and what they now have. For example: They see the old terrain in red or orange, and the new terrain in green, so they understand what work they have done. Then the user very clearly sees what they have changed, added, and removed. This way they know when they are being destructive, and when they are not being destructive, if destructiveness is truly unavoidable for technical reasons.

Lastly, someone mentioned an 'uh oh’ button. Basically, giving the user a way to always go back, without having to worry about losing work. So no matter what they do, they always feel safe, which can be helpful for creatives. This can be done by having save states of the editor together with the file they are working on, or other such backup files of what the user is working on, so that the user can go back to any previous work whenever they want to. Knowing the editor is always automatically backing up their work is very helpful to make them feel safe, as if they are working much more in a non-destructive system, even if under the hood a lot of destructiveness is happening in-between the various backup files. That way they can still always load a previously saved version of their file, and take a look at what they had before, or even copy and paste what they had before into their latest file.

4. Versioning and getting builds & tools to internal users

Next, what are good ways to version and get builds and tools to your users? Someone mentioned that it can be helpful to only get and load very specific parts of the tools and the engine, and that their midsize studio was doing this successfully. Not every person has to use every single part of their tools or engine, as individuals have specific jobs and responsibilities. So when they only load the specific parts they need, and only update the specific parts that they need that can help speed up the process of giving people builds, as the update sizes are much smaller. Though in all cases you would still need the ability for a user to update everything, in case it is ever necessary.

Additionally if there are particularly difficult or dangerous things users can turn on, it was mentioned that it can be nice to have a danger section that clearly shows there are dangerous options, through progressive disclosure. Such a panel you can unlock, or a box you have to check to indicate you know what you are doing. So users can turn those on if they want to, but they will not accidentally do so, and only those dangerous options have large data sizes, or complicated setups.

Lastly, getting builds & tools to internal users can require various systems, but to a user it should always be a ‘big green button’. Users can click that button, and they automatically get what they need, with no need to think about how many servers, build versions, or systems there are under the hood. That way they always get the right builds and tools fit for their tasks. This takes more time up front, as it requires a UI and a wrangling of the systems underneath, but frees up a lot of time afterwards as all users (including new hires) can get what they need without having to ask anyone questions.

5. Displaying information in Unreal, how can you make it better?

Someone asked how to display information better in Unreal, for internal users who need information while editing content. Not any specific scenario, just in general for visualizing data in Unreal. Immediately someone mentioned editor utility widgets, which are made in Blueprints. These allow for UI to be built and shown inside the editor, allowing people to visually set up information that users want. As they are in Blueprints it also allows users to edit those themselves, if they are slightly technical, which was found to be very helpful.

From a classic UI perspective, ImGui was still the mainstay in the room for showing data quickly, simply, and fast.

Having information displayed in Unreal can also be good to do spatially, inside the level the user is working in. That way the user gets the spatial context of what they need to know, and also how and where to apply it.

Then someone else mentioned: Does the information you want to give users have to be shown in Unreal? For example if you have a lot of dialogue lines that you need translated or localized in a specific way then Excel might still be a way better way to view them. In that case, make sure that accessing that Excel sheet is very easy, contextually from Unreal, so it is easy to find and use. Sometimes, having a separate tool for specific information can be better than cramming everything into one view, especially if at some point the 3D view is covered in text and data that only 1% of users need, and 99% of users are bothered by.

6. How to handle requests that will cause performance issues

How do you handle a request that, if you were to follow through on it, you likely think performance issues would arise from it? For example: An artist will ask to see and render an render an entire level in a particular way to easily edit it, and while that may be technically possible, performance in the editor would grind to a halt if they were to do so. How do you handle such a request? In such cases it is best to ask why five times to really find out why the users think they need it. Maybe you find out there is a different issue going on, or maybe they truly need it, but either way asking more questions will help you better understand how to help them. If you only ever deliver exactly what the users ask for, then you will just end up in trouble with many features that make no sense together. You would be delivering features, instead of workflows. Similarly if you listened to every request from playtesters, every game would feel weird to play. A user’s feedback is not always correct, but the place it comes from (if they are your target audience) is important to know, so you can find out what the real underlying issue is.

If you are going through the details with the user, and you find out they still need to do the thing that makes you worried about performance, it becomes important to look at how much you can solve the issue. Maybe 90%, maybe 80%, so not everything is fixed for them, but a big enough portion that their workflow is improved while keeping performance stable.

Next, someone brought up being very WYSIWYG with your game, if possible. Basically: If your game works a certain way while running, to then make sure that your editor also allows editing in similar ways. Essentially trying to mirror their UX as much as possible so that folks have an understanding of how to do things in the editor, which then makes it much much easier to also have those conversations with them about the five why’s. If the UX of the editors, tools, and workflows is easier to understand, conversations about those topics will also become easier to have. This is sometimes much harder to achieve than others, but it did work well for someone at the roundtable.

Lastly, if there are issues with performance on things such as big levels, make sure you are using a automatic grouping or layering system so that users can easily turn on and off of various parts of levels. For example, they may want to see all the geometry, but they turn off the rendering of art assets. Or maybe they only want to see the debug volumes like triggers and lights, so they can easily turn off all the rendering of geometry. Both of those scenarios make sense at different periods of level creation. It depends on what the user needs at their moment in time so allowing them to set for themselves what they do and do not need to see can can really help with performance. If, in the end, they do decide they need to see everything, there is a degree of them needing to anticipate their frames per second (FPS) will be a bit lower than usual. But denying a users’ request outright for performance issues is a step too far. First find out how important the issue really is!

7. My users are silent, what do I do?

Someone asked: “My users or silent, what do I do? How do I get feedback?” The main answer here was mentioned by many folks at the roundtable: Sit behind people. You have to actually sit behind them and see how they work. Understand what issues they are running into by literally observing them. See what they are actually doing, because even if they talk to you about what they think, what they actually do may be completely different.

Many users will also suffer in silence so it is important to look at if they are suffering, even if they are silent. Then you can find out how and why they are suffering. If you are doing this remotely, then recording a timelapse can be very useful to see how people work and if there are any issues. Hours of recordings can then become just a few minutes to view. While you may not get all the information you need from such a timelapse, you will be able to get more pointed questions to ask those users.

Someone also mentioned making a survey, such as in Miro. For example by visually showcasing the pipeline to give people an idea of what the pipeline looks like, and then letting them put notes about where they get stuck, frustrated, or are happy. This is especially helpful for more visual thinkers like artists, who want to explain where they get stuck, but may find it difficult to explain that in words.

If folks are working remote, a screen share to see how people work is helpful too. Either one on one, or even a group of folks seeing one person work. This lets you validate the pain in the view of the overall team, and also lets them share important workflows with each other.

If many of your users are silent, it can be also good to look at why they are silent. It may be because while many of them came to you with their issues, nothing was ever done about those issues. Eventually those users are no longer going to come to you with issues, as they want to spend their time more wisely. They will start to ‘deal with’ any issues they are given, expecting those issues to be ‘normal’, and that nothing they can say or do will resolve them. This is a very toxic situation for everyone to be in, but nevertheless, it happens at many studios. So when someone comes up to you with an issue, make sure to at least look at it look at it and at least come back to that user and let them know what you can and cannot do. You cannot resolve each issue, but letting them know why you cannot resolve their issue will make them at least feel heard, and come back to you with future issues. If you say something like: “We can’t do this, and we can’t do this, because of this and that reason.” then folks will appreciate it. If you do not do this, people are simply not going to come to you again, and you will miss out on critical information.

Having ‘Champions’ or ‘Strike teams’, can also help so that there are always folks around the team that users can easily talk to. Users then know who to approach about issues at all times. While an engineer may be dangerous to interrupt, a Tool Designer is usually much easier to flag down and ask questions to. That person can then also really dig into the users’ issues, ask all the why’s, and give the engineers a clear cut solution that fits into existing workflows as well as have discussions with them about what fits well into the existing software architecture.

Lastly, make sure to ask people: “If you had a magic wand, and you could do anything ,what would you do?”. A big problem with tools and editors is that an artist cannot easily know what is difficult or hard to do for an engineer, and an engineer cannot easily know what is difficult to do for an artist. So you have to have a conversation in which nothing is off limits, as what may seem complicated can be easy, and what may seem easy can be difficult. Suggesting a ‘magic wand’ to an artist makes them think about their own problems and solutions more out of the box. If their solution really is magic, you can then at least still walk backwards from there to a realistic solution. Starting off at a magic wand is really helpful, so you can have a simpler conversation about the actual issue at hand that the artist is running into.

8. How do I move from a UX design role, to a Tool UX Design role?

What came up the most in this conversation is that Tool UX Design is just so different from regular UX Design. It is a different way of thinking where you are not servicing the general public, and instead you are servicing professionals on a day-by-day basis. While a flight booking app for the general public may have to be very simple in use, with very few buttons, professional use tools 8+ hours daily, and those are sometimes improved by having many buttons visible. The basics of UX are still important to know about, but are applied in very different ways. Classically in UX design, this is sometimes seen as a difference between ‘UX Design’ and ‘Service Design’.

Someone also mentioned that you have to be able to talk to many people, such as engineers, artists, designers, producers, everyone. You may get weird information sometimes that does not make sense or contradicts itself, where one engineer will say something is possible, and another will say something is impossible, and you have to give them ‘five minutes’. It is a rule someone at the roundtable had created for themselves where if they talk to an engineer, and they get told something cannot be done, they always give it five minutes. Usually after that time, with some more thinking, that engineer will say “Hmm, actually, but if we did it in this way…” and there suddenly is a solution possible. Giving conversations time, and knowing when to both speak and be silent are very important for a Tool UX Designer. Communicating with many roles is critical, but the communication with engineers is usually the toughest hurdle. You don’t have to learn how to program, but having a basic understanding of systems will make it much easier to have such discussions with engineers.

As a Tool Designer you also have to understand many more workflows, practices, and other tools. This is very time and energy intensive, and necessary for proper communication between so many different roles. So while both roles involve UX design, moving from one to the other can be very different, especially as each company, project, and culture, thinks differently about what ‘UX Design’ actually is.

9. Usual Tool Design patterns, best practices, and surprises

Someone asked if there are any usual UX patterns and best practices. Personally, I dislike the term “Best Practices.” I understand why folks ask for them, but they do not exist. Think about the inverse: If there were best practices that would always work well, then all companies would be using them to always ship successful products. They don’t, they all fail sometimes. Instead: There are practices. Learn about as many as possible. Then pick which ones are best for your team, your project, and your company. And if one doesn’t work, change it. Keep iterating until you find what’s best for you. You iterate your product, why wouldn’t you iterate your company? Asking someone else about practices is great to learn more. You will see more possibilities that you can try. But asking about “best practices” will always, if the person you’re asking has experience, result in one answer: It depends.

One particular practice I like is: Do not make design decisions in meetings. Make sure that if you’re discussing a topic that you do not make judgement calls right away. Often times folks get stuck thinking about how big a tool could be, or all of the amazing things that it could do. Instead: Service exactly what the user needs at first. In the design meeting think about four or five things that you can do, and then try those out and give them to users. The final design decision is not your choice, it is the users’ choice. What you think will work well, may end up being terrible. What you think is terrible may end up being fantastic for users. If you only ever make decisions in design meetings, you will lose out on the critical information you need from user research.

Another thing mentioned by someone at the roundtable was to not try and make a Swiss army knife tool that can do everything. Splitting up tools so they can be individually used, individually updated, and do not always rely on each other can be helpful depending on your workflow needs and software architecture. Every decision has tradeoffs, and this person found that trying to squeeze everything into one tool often means having to make many tradeoffs that become less and less worthwhile.

10. How to better deploy engine agnostic tools

Lastly, someone asked how you can deploy engine agnostic tools in a way that works well for internal users. For example, if you have a bunch of tools that are third-party, plugins for DCCs, how do you make sure users get the latest versions? Again the ‘big green button’ made an appearance in this conversation. Even if the systems, servers, and tools are all separate, the user does not care for that and should not need to know about that. They should be able to press one big button, and then get the latest engine, tools, and also plugins for DCCs. This is much easier said than done, but it is the best way to make sure the entire pipeline always functions for the team, which is a critical role for any tools team.

Also, ask yourself whether your tool need to be agnostic. Sometimes Excel is best, but sometimes a spatially in-context in-engine tool is best. Each situation has its own pros and cons, and it can be good to look at old tools and re-decide how important it is to have them be agnostic to your engine. Sometimes, having all your different tools in one editor, all in one pipeline, with all workflows present, can be helpful, while other times it can be detrimental to everyone’s workflow or your own software architecture.

If you do have to have third-party tools, make sure you have a launcher of some kind, with a big green button, that makes it so users can easily see what is updated, what is not updated, what they are using, what they are not using, etc. Essentially that launcher itself is also an engine diagnostic tool, which from its central agnostic place can grab all the versions, updates, and tools the user needs. It becomes not just a way to deploy tools, but also to view, check, and be informed of which tools are in your pipeline, both for you and all your users.

Thank you

Last but not least a big ‘Thank you!’ for everyone that attended the Tool Design Roundtables at Devcom 2025. I sincerely appreciate everyone who shared their own stories of both joy and woe as we all strive to create better tools & workflows for everyone. I hope to see you all again next year!

If you want to learn how to host a great roundtable yourself, here is a guide.

Subscribe below to get updates when a new post is published.