How to host a good Roundtable at a Conference

Roundtables are incredibly helpful for conferences as they provide an opportunity for attendees to be talked with, instead of talked to. Attendees of the roundtable can raise topics themselves, and everyone at the roundtable can then discuss that topic together, not just a speaker or panel of speakers. This conversational element makes for an environment in which everyone at the roundtable is brought together to discuss topics that they prefer, for however long they prefer. This makes sure that the topics discussed at a roundtable are always of interest to the attendees.

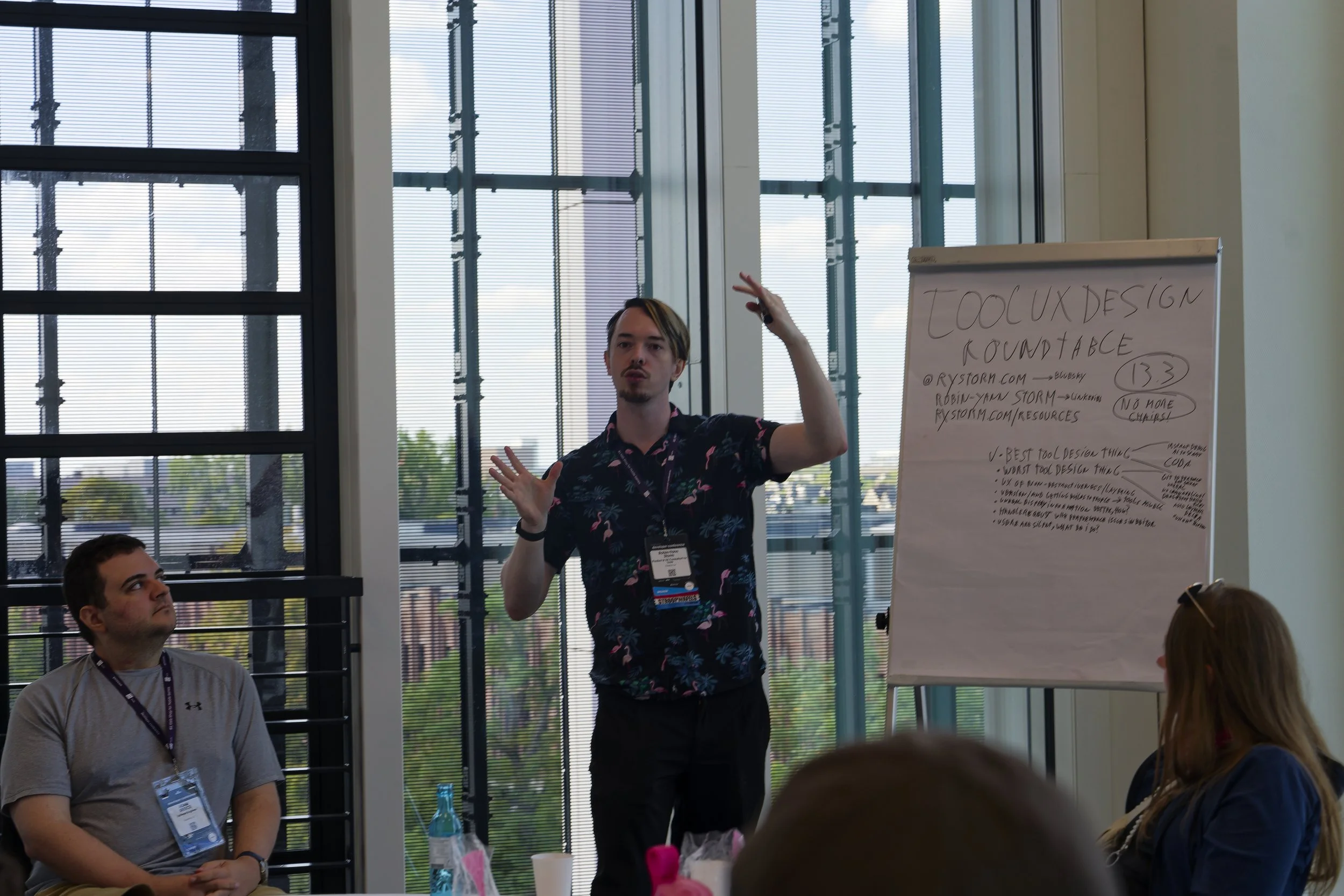

I have hosted the Tool Design Roundtables and OpenUSD Roundtables at the Game Developers Conference (GDC) for many years., the Tool Design Roundtables at Gamescom Dev for a few years, and have held roundtables at various other conferences around the world. My roundtables have consistently been ranked as the top 5 roundtable sessions at GDC, and I get lots of folks saying they love to visit them. Because of this, I also get a lot of people asking me how to run a good roundtable, because they have visited other ones that felt chaotic, noisy, and sometimes even like a waste of time. That is a very bad feeling when you are paying a lot of money for a conference ticket!

So, here is my advice on how to run a good roundtable.

The Roundtable Setup

First of all, it is important to understand the definition of a roundtable. It is not a panel, and it is not a talk. A talk has slides, and a panel has multiple speakers talking to each other on stage. A roundtable has a single host, who is the moderator, and the audience gets to discuss what they prefer to discuss. I stand firmly behind ‘one moderator’ being a set requirement that can only be crossed over due to accessibility needs where someone needs assistance to run the roundtable. The reason for having only one moderator is because everyone can speak in a roundtable. Anyone who shows up, anyone in the audience, can raise their hand and contribute to the conversation. That is what makes a roundtable: One host, yet everyone can contribute. The purpose of a roundtable is community building, giving people answers to specific questions they have, and creating a safe environment to share and learn. If there are multiple hosts, it just becomes a panel with Q&A.

When I start my roundtables, I first explain in two sentences who I am, and my history. This is important as the audience has to understand who is moderating the discussion. Next, I tell everyone how the system works: If you want to talk, you raise your hand. If the moderator then points at you, or calls you by name, you talk. If you have not been pointed at or called out, you do not talk. I then let the audience know I will keep track in my head of what hand was raised first, second, etc, and that I will get to these folks over time. Sometimes a simple nod can suffice so that the audience member knows they are next, so that they can lower their hand. Nobody likes to have their hand raised for minutes at a time, so I can also point at them with one hand, and make a number with my other hand, to indicate I have seen someone, and when they are next.

This process, clearly outlined like that, puts the audience at ease. Everyone knows what to expect. Everyone knows how to participate, and how to stay out of the conversation if they just want to listen. This clarity has to be created if your roundtable is to be both helpful, and fun. It is best if it is both!

Also, it’s good to tell the attendees that they do not have to look at you, and that they can look around the room while talking. You, the moderator, will also be looking around the room for hands, so it is not like you can keep locking eyes the whole time. Then, let the attendees know to point at someone else if you keep missing their hand being raised. When roundtables get very large, like 50+ attendees, it starts to happen that you miss someone in the sea of people. Especially if they are short and have a harder time reaching their hand up high, or if they are behind you.

Wait, behind you? That’s because you are standing up. As a moderator you are not sitting down, and you are not behind a laptop writing notes. You are moderating the roundtable. That is why you are there! So stand up, speak up, and take control. You need to be the presence that makes the roundtable flow.

Iron Fist, Velvet Glove

This roundtable setup makes it possible for big and great conversations to happen. Nobody can dominate the conversation, nobody is elevated above the conversation, and everyone can participate. It also makes sure that one person is in charge, who can protect and guide the conversation. That first part, protecting, is the most critical of any roundtable host. The most common complaints that attendees of roundtables bring up, is that the conversation is unstructured, confusing, noisy, and that they did not learn anything. The best way to solve this problem is to host a roundtable with an iron fist, and velvet glove.

You need to be incredibly kind to the audience, and sweep them up in the excitement of talking about the roundtable topic. Maybe it’s animation, UX, or narrative, whatever it may be. This is the velvet glove. You also have to make sure that if someone talks out of turn, without raising their hand, or starts whispering to people next to them, that you squash that with determinism. The first time it happens, let them finish their sentence if they are not talking over someone. But if they speak out of a turn a second time, or speak over someone: Do not hesitate, do not wait. Immediately, very politely and diplomatically, ask them to raise their hand if they have something to contribute. Make it known right away, in the most friendly manner, that there is an order to the roundtable. The process must be followed.

You may think that whispering should be ok, and it is true that a sentence or two can suffice. Though you will quickly bump into folks who continue this for much longer, and at that point you have to make sure it does not spread around the room. If one person has to raise their voice to go over it, then others do too, and this downward spiral gets out of hand very quickly. Also, whoever is sitting next to the people whispering will have an incredibly hard time hearing the rest of the room. It may not be loud to you, but it is loud to whoever they are next to.

Another reason that it is important to quash whispering instantly, is that usually it is much better for a roundtable to be hosted without microphones, except for the moderator. Running microphones around costs valuable time, and cuts into natural conversation. Every few sentences you have to wait for a microphone to either be walked, or loudly ran, to the next speaker. Especially in big rooms this becomes an issue quickly, and throws off natural conversation. Throwable microphones, in soft cubes, can prevent this and sometimes work well for smaller roundtables, but for large rooms it is too much of a drag.

Similarly, do not use a ‘stone’ or ‘speaking object’ to show who is currently talking. This takes time to move around, cuts into conversation, and is much to intensive to control and keep track of as the moderator. A physical object can be passed without your control, so suddenly people are speaking that had not raised their hand!

Instead, the moderator has full control. They need to understand who is speaking, when, and who is next. They need to listen to the conversation and look at what hands are being raised, and in what order. This is what makes hosting a good roundtable so difficult. The moderator is what makes or breaks the roundtable. You have to be jovial, you have to be excited, you have to be happy, you have to keep control, you have to know the subject matter well enough to be able to host for the topic, it’s a lot! You have to get energy into the room!

Further setup

In the start of the roundtable I also tell folks what this roundtable is about. For example I say it is about Tool Design, not Tool Engineering, so do not mention CMake or other technical things, as those are a better fit at another roundtable. Or, if I am hosting an OpenUSD roundtable, I clarify what OpenUSD is, and tell folks any topic is fine as long as it directly related to OpenUSD.

Then, I say that if they are bored, to please feel free to leave, and that you won’t hurt my feelings if you do. It rarely ever happens that someone leaves, but I have sat in roundtables and talks that just… didn’t feel like a good spend of time. It hurts to leave and show the speaker you are leaving, but by clarifying it won’t hurt you, you again give people breathing space. They can leave if they want, and that’s ok. Sometimes a session just isn’t a good fit, so I always tell folks I would rather you spend your time doing something you enjoy, than steaming in disappointment for an hour. On the other hand, I have also had folks accidentally join one of my roundtables, and stick around because they enjoy it so much!

I also tell folks to say their name and company they work for when they speak for the first time, which is when they have raised their hand and get called on to speak by the moderator. The reason a first speaker should mention their company when they first speak is so that this gives everyone a grasp of the scope of their answer. If the company is huge, then we know what worked or didn’t work for their size. If the company is small, then we know what worked or didn't work for their size. This is critical to the discussion, as particular advice given by an attendee may work very well for a big company, but terribly for a small one.

I also let attendees know that if they cannot be heard in the room, that they have to speak up. I usually do this by hand gesture, slowly lifting my hands up in front of my chest. This is the best way to do it, as you do not want to interrupt the person speaking by saying ‘Please speak up.’ as it makes them lose their train of thought, and interrupting folks feels terrible. Clarifying the hand gesture at the start makes it so that everyone also understand when speaking up is being indicated. Sometimes, someone just has a very low voice, and they cannot speak louder. This is, again, where the iron fist, velvet glove comes in: Because the room is entirely quiet except for the person currently speaking, they can still be heard!

I then clarify that I take about 5 to 10 minutes per topic. I may cut off a topic, which is not against you or against the topic itself, but just because we have limited time and want to cover multiple topics. A great part of roundtables is that everyone gets to meet each other, not just a single speaker or a panel, but everyone in the room. So I clarify that if you want to discuss a topic further after the roundtable, please go talk to the other folks who were discussing the topic after the roundtable has ended. This also creates much more of a community vibe at the conference. Roundtables create great icebreakers for conversation.

Lastly, I clarify I may not always call on you if your hand is raised. Sometimes a new person, who has not spoken before, raises their hand. I want to make sure to get new voices in, so I will prioritise them, especially if we are already 30 minutes into a roundtable.

All of the above may sound like a lot of setup, but it takes less than 2 minutes to go through these instructions. Again, it is a necessity, to tightly, yet nicely, run a roundtable. Rules have to be clear, and followed.

Do not ever start a roundtable with an introduction round for everyone there. It takes up half the time, not everyone wants to speak as some folks are just there to listen so leave them in peace if they want to, nobody can remember everyone's name and profession anyway, and there will always be a person or two who introduces themselves with a much too long story. The only case where you can do an introduction round is if the roundtable is 6 people or less, which it hopefully shouldn’t ever be.

Starting the roundtable

After the setup has been made clear, in the case of the Tool Design Roundtables, I try to get the usual two questions out of the way. These are questions that get asked every single roundtable by an attendee no matter what, so it is best to get them out of the way immediately. These questions are: What roles are in the room, and what UX/UI tools do folks use at the moment? For the roles, I simply call out a list of roles: Tool Designer, Tool Engineer, UX Researcher, Tech Artist, Producer, etc, and ask folks to raise their hands if they are that role. Always be sure to ask “Any role I didn’t mention?” so folks can chime in with their specific title or role. Nobody can decide what any particular role or title is called anyway, especially in UX and UI. Replace these questions with whatever things always come up in your roundtable, so you do not always get the same discussions over the same topics again and again, which is annoying to recurring attendees. If it is your first time, just wait until you have done one or two roundtables so that you know what the repeated questions are.

Then for the question of what tools folks use, I similarly go down a list: Figma, Sketch, Miro, Adobe XD, Balsamiq, etc. Again I ask “Any software I didn’t mention?” at the end, in case someone is using a new or custom solution.

Then, with everyone having done some body movement due to their hands having been raised at least twice, I start off with two icebreakers that I have written down beforehand on the paper or whiteboard in the room:

What is the best thing that happened in Tool Design for you this year?

What is the worst thing that happened in Tool Design for you this year?

I start off with question 1, repeat it, and then ask people to raise their hands if they have something to share. We hear about some of the great things, such as an awesome new tool that worked really well, or a new Tool Designer hire that turned out great, etc. Then, after 3 or 4 of these, I summarize all the ones I just heard in a very short way. For example, I say: “Looks like making tool A worked well for that studio due to the environment artists needing X, that hiring a tool designer greatly helped the development of tool B, that adjusting help pages prevented issues at studio Y, and that a new design system in Figma saved time at studio Z.” This is very short, but the summary of what everyone had just heard makes the takeaways so much easier to remember. This is also what requires the person moderating the roundtable to have deep experience in the topic of the roundtable: So that they can summarize. This summarization is what makes the information stick, and so you have to keep it in mind. Running a roundtable is tough because of this, but that is why it is a dedicated role.

Then I move to the second question, and go through the same process.

After that, in less than 5 minutes everyone is warmed up. I then open things up: Who here has a question that they want to ask the room? Attendees raise hands, you go through them one by one, and write down their question on the board. Try to have 3 questions per 30 minutes. So for a 1 hour roundtable, 6 questions. For an hour and a half, 9 questions. Write them all down, and after that, you say that any more questions we can get to if we get through these ones with time to spare.

If the question that am attendee asks does not fit the topic of the roundtable, or is unclear, do not hesitate to adjust it slightly. Ask “Do you mean like…?” or “So your question is…?” and fill in the blanks yourself. Paraphrase questions if you need to. As a moderator you should know the topic well, so you will understand what they are trying to say. Not everyone is great at shortly summarizing their point, so sometimes you have to cut it down yourself. This is fine, and expected. You are helping the attendees out as the moderator.

Then, you start. You repeat the top question on the board, ask who asked it, see if they have any additional info, and then ask who wants to comment on this. Time to start counting hands, summarize information, and cut down on any interruptions!

It’s all about vibes

Of course someone will speak out of turn sometimes. Someone will whisper a bit. Someone will ramble on and on about their question, or an answer to the question. Remember the Iron Fist, Velvet Glove. When a question or answer is rambling on, and you have to vibe out if it is getting to an end, you can interject by saying: “And so what you mean is…?” as this primes the person to get to the point. It’s not foolproof, and if the rambling continues you have to ask again, or be more explicit about getting to the point. This will differ with each person, each roundtable, and each topic. It’s all vibes based. You have to vibe out what the conversation needs, and what your attendees need. You, the moderator, are singularly responsible for a good or a bad roundtable. I have had packed roundtables with a lot of having to handle the crowd. I have had small roundtables with close up conversation. Both can work totally fine, as long as you as a moderator have taken the action to make the roundtable good.

Sometimes a question cannot be answered by the attendees. Nobody raises their hands to answer it. This is sad, but it happens. Ask the attendee who raised the question to ask it in a different roundtable, or talk to you, the moderator, afterwards. At this point, you can also bring in your own anecdotes or questions. Sometimes that helps get the other attendees going.

Also, when you start to cut off a topic and move to the next one, ask the original question asker: “Did your question get answered?” Let them confirm, yes or no, so that you know if they were helped or not. If you cut off a topic without the asker being satisfied, it puts a serious damper on their mood. Sometimes they cannot quite confirm if the question as answered, but they will say ‘Not exactly, but I will check with that other person over there later’, and that’s totally fine. Sometimes it takes more time and more discussion, which can happen outside of the roundtable’s time.

Not rules, just guidelines

All of what I wrote above is just my guidelines for a good roundtable. Others host good ones too, and do things differently, but, not much differently from me. Always one moderator, always one question at a time, and always stopping chaos instantly. If you do that, you will have a great roundtable. I have also learned a lot from other great roundtable hosts, like Jeff Hanna and Geoff Evans, who have respectively hosted the Tech Art roundtables and Tool Tech roundtables for many years at GDC. Geoff also wrote about how he hosts his roundtables a few years ago. Jeff Hanna is even going to be hosting his 20th year of Tech Art Roundtables in 2026!

Also, if this is your first first roundtable, you will just have to feel out what does and does not work. Even I, when I started up the OpenUSD roundtables after already having hosted the Tool Design roundtables for many years, had to figure out what worked best for a different audience, and a different topic. The iron fist, and velvet glove, still apply in all cases.

Thank you

Thank you for reading the whole post! This advice has helped a few folks host some of their first roundtables, and I have been so glad to see them do it! You can download my GDC roundtable example submission here, which is the format I submit for my GDC roundtables. Feel free to contact me at Bluesky or Mastodon, or LinkedIn if you have any questions.

Subscribe below to get updates when a new post is published.